--Gouldner (1979, p. 8)

“Because all concepts are approximations, this does not make them ‘fictions’. . . [; in fact,] only . . . concepts can enable us to ‘make sense of,’ understand and know, objective reality . . . [; at the same time, however,] even in the act of knowing we can (and ought to) know that our concepts are more abstract and more logical than the diversity of that reality.”

--Thompson (2001, p. 461).

“Reality” is too complex to fully capture in abstractions. Every study selects particular aspects of the world to emphasize, necessarily leaving the rest in a shadowy background. In other words, we must choose what is generally called a “theoretical framework” to guide our analysis. This choice helps determine what we “see” in our data—how we make sense of what happened in a particular context. In fact, one of the first questions a dissertation advisor will often ask a new doctoral student about their dissertation is, “what’s your theoretical framework?” Despite the importance of this choice, however, it is a process that is rarely examined in the literature.

It seems to me that questions about the genesis of theoretical frameworks are central to the place of foundations in educational scholarship. Foundations classes (in sociology, philosophy, history, etc.) represent one of the few places in graduate education where students are likely to encounter a range of different and contrasting theories.

In my limited experience, graduate students often acquire theoretical frameworks in extremely problematic ways. The most common source of a framework is probably in the work of one’s advisor. In my school, there was a recent spate of dissertations using Bandura’s theory of “self efficacy,” reflecting the interests of a small group of professors. I imagine other graduate students walking up to a Borgesian bookcase of theories, skimming through them until one strikes them as useful: “Hmm . . . . Barthes? No. Bakhtin? No. Bernstein? No. Oh, Bourdieu! Okay, good.” I rarely see early career scholars think in any sophisticated fashion about the plusses and minuses of particular theoretical frameworks, about what each illuminates and obscures (although this may be a product of my particular university).

Let me propose, speculatively, a simple schematic theory of how scholars should construct theoretical frameworks. It seems to me that there are three key axes that determine whether one has a more or less sophisticated approach to theory in the context of a study.

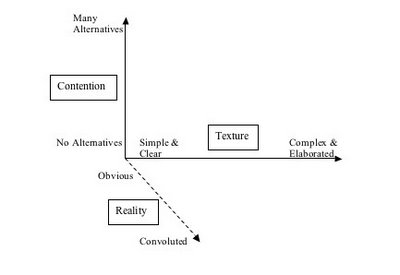

Let me propose, speculatively, a simple schematic theory of how scholars should construct theoretical frameworks. It seems to me that there are three key axes that determine whether one has a more or less sophisticated approach to theory in the context of a study.--The first axis I call “texture.” As one moves out along this axis, one becomes increasingly conscious of the internal tensions and complexities of a particular theory. Depending on the internal sophistication of a particular theorists, there may be real limits on how far one can move in this direction.

--The second axis I call “contention.” As one moves out along this axis, one increasingly grapples with critiques of a particular theory and, in the farther regions, begins oneself to consider the ways other theories might complicate the conceptualizations of a particular theory.

--The third axis I call (with apologies to postmodernists) “reality.” Moving out along this axis one becomes increasingly sensitive to the internal texture of the data one is examining, of the aspects of the world that are and are not included, and of the alternate ways one might conceptualize relationships between different aspects.

Of course, this graphic is much too simple—but like all theories I think it illuminates something important about the nature of academic writing and the operation of theoretical frameworks. (One key limitation of this picture is the straightness of the different axes. In actuality, as one moves out along the axis of “texture,” for example, one necessarily moves closer to both other axes, since teasing out complexities will increasingly require reference to the writings of others and to unexplained aspects of the context under examination. Thus, imagine that all of these axes curve towards each other (which I don’t know how to do in my simple drawing program.)

Within this schematic, there are different ways that one could be sophisticated about one’s use of theory. One could look at one particular theoretical framework (or theorist) in detail, exploring its complexities and tensions. One could address the broad range of contrasting perspectives that might reveal limitations in one’s theory—perhaps leading one to draw from more than one theory at the same time. And one could take a focused “grounded theory” approach where one seeks to understand the richness of a particular situation or data set. Each of these choices, and combinations of them, place one at a different point in this three-dimensional space.

(Of course, as Gouldner points out, above, moving too far out along an axis can lead one away from understanding into incoherence.)

I want to argue, then, that scholars who find themselves near the vertex are generally those with inadequate theoretical frameworks. These are scholars who:

--draw from a single simplistic theory;

-- tend to gloss the critiques of others; and

-- generally don’t look beyond the aspects of the world that their preferred theory emphasizes.

Scholars like this have probably either accepted without much critique the perspectives of their advisors, or have chosen theories that reflect conceptions they brought with them to a particular topic in the first place. (In a Gadamerian sense, their theoretical choices have neither helped them identify nor put tension on their own prejudgements).

What does this mean for graduate education?

In the first place, I think it indicates that we should insist that even students who are not focused on “theory” have a relatively sophisticated understanding of the internal texture of their theoretical framework they have chosen.

Second, it seems to imply that acquiring a sophisticated understanding of a single theory is not sufficient. It seems to me that we should insist that students achieve an understanding of at least one other different theoretical perspective that can put tensions on the first. It is only possible to understand the limitations of one framework when one examines this from the perspective of another. Those of us with experience with a range of frameworks can point them towards an alternative that might usefully challenge their current perspective.

Finally, we should be suspicious when students’ studies indicate that a particular simple theoretical framework can be used to explain a particular data set with no difficulties. Reality is _never_ accurately represented in such a simplistic way, and when scholars imply it can be they fundamentally distort our ability to understand the world and to apply the findings that emerge from a particular study to the always somewhat different complexities of a different context.

The issue, here, is the _minimum_ we should expect from doctoral students before we are willing to certify that they are able to adequately conduct research, and what role foundations professors should play in this process.

Gouldner, A. (1979). The future of intellectuals and the rise of a new class. NY: Seabury Press.

Thompson, E. P. (2001). The essential E. P. Thompson. NY: The New Press.

5 comments:

This posting excites me, as we have wrestled with just these issues in my own department. Often many students in my college will say they want to do a "qualitative" dissertation, and what they mean by this generally comes from a few authors, such as Patton. Other students say they will do quantitative studies, and for many in educational leadership or related areas, this means simply survey research and some rather basic inferential statistics run off a computer package.

The larger question, for me at least, leads to how much educational research is guided by psychology, or as my university calls it, "psychological sciences." Our own "research methodology" area is lodged with our ed psych professors. None of them do any philosophical, interpretive, or qualitative research, but manage to give a nod to these traditions in the research methodology courses all graduate students must take.

So, the role for foundations professors would be, in my situation, to boldly develop our own methodology and research courses, which we are about to at least think about. Getting them wedged into an already tight graduate curriculum will be the rub, however.

I agree that there are opportunities now for foundations folk to embrace the qualitative science domain as an emerging natural philosophy.

I feel fortunate to have been exposed to a range of qualitative orientations at Tennessee. I got the excellent Ron Taylor (adverstising) treatment in a couple of courses, the existential-phenomenological (Duquesne) work group of Howard Pollio (psychology), the ethnographic emphasis of Demarrais (critical ed. foundations), and the quiet and intensely-thoughtful zen of Amos Hatch in early childhood studies. Very fortunate, indeed.

Hatch, by the way, has the best book (Doing Qualitative Research in Education Settings) that I know of in terms of a beginning doctoral guide for doing a qualitative study. Like you, Aaron, and many others who have become impatient with grad students’ theoretical impatience, Amos’s book begins with an insistence that a methodological grounding must be understood and explained before one can claim it. And unpacking assumptions is the first step. Plus he takes us into four alternatives from post-positivism to post-modernism, showing respect for all along the way.

I used his book with the Berg book in a beginning qual. Research course, and students found much more in Hatch that was usable and thought-provoking and insightful. Me, too.

Qualitative studies fits with foundations? It seems that we are at a juncture where scientifically-based has been defined by ideological zealots as quantitatively based. It is as if the paradigm wars that fought in the late 80s didn’t happen. Of course, history is unimportant to those intent upon building a future based on an imaginary past. In any event, verstehen-based qualitative studies need to be inherited by those interested in knowledge, rather than data. After all, the search for a methodology to express a qualitative science will not be invented by those incapable of imagining such a thing. And a qualitative science is exactly what we need in order to get us out of the ditch.

I'll skip the questions about the 'reality' axis (and whether it makes sense to compress the questions social constructionism and postmodern writings raise into one dimension) and head directly into the obvious gap between the abstract description of a theoretical framework and the sort of interests an historian has in (social) models: what can a model explain?

The greatest weakness I see in education doctoral work I read is the inability to formulate clear and meaningful research questions in ways that students can answer in the time they usually want to take for a dissertation. This perception may be a consequence of my institution, but I was socialized (perhaps too well) into the model-explanation link. "If you have a good model, it needs to explain things and not just sit there looking pretty" is the voice in my own head. Sometimes, I see doctoral writing that has plenty of pretty theoretical writing but no grasping of the nettle, so to speak, to explain what the different frameworks suggest about possible answers, alternative hypotheses, and elephants in the room that we're usually ignoring.

Incidentally, I think those who laid claim to the mantle of 'qualitative research' in the 1980s did themselves and all of us a bit of a disservice whenever they claimed (or continue to claim) that qualitative methods had exact parallels to psychometric properties that dominate educational research—barometric textual reading is the equivalent of reliability, someone could have written, or, to someone else, we can use rehydrated conclusory notes as the parallel to validity. That parallelism narrows warrantable claims to the same (rather clever) research tricks of psychologists instead of grounding qualitative research in larger questions of what makes for rigor.

To respond especially to Sherman, I actually looked up the Hatch book just to get a sense of it. It's actually available online at my library. Anyway, it looks like a wonderful book. And. . . it doesn't really get at what I think I'm trying to get at, here.

More than a broad sense of the available theories, which Hatch seems to present (he can't really do more),I am interested in what level of sophistication we should demand from students as a minimum. And this, I think, is what takes it out of the realm of "qualitative researchers" and into the realm of foundations more generally. Because it is in foundations that one might get access to the texture and contention around particular theoretical frameworks that is generally lacking (but not entirely, to be fair to our C&I collegues, for example) elsewhere.

Of course, Sherman is right that many doctoral students can't really figure out what kind of question they want to ask, and this problem seems to complicate the schematic picture I was playing with. Although it also might be about a theory which is in one world, and a set of data that is in another, and the twain never meet to put tension on each other. But maybe it's time to leave my little thought experiment behind.

Actually, in my limited experience at a not first-tier place, I've seen many dissertations (even in late stages) that are really just summaries of what students have read, and/or make a range of different arguments that never seem to cohere.

Also, like Rud, I think, I pound my head against the desk every time I see a methodology section that consists of block quotes from Patton, Merriam, et. al. that make vague statements about qualitative research.

And I don't think quant people can get away without having sophisticated theoretical frameworks, either. What they call theoretical frameworks often look as schematic as my little graph--and is this sophisticated theory? Does it matter? I think so. They can't really critique their own conclusions from a perspective that is significantly different from their own. And they often seem to have little understanding of the potential internal tensions, ambiguities, etc., of their codings. But maybe I'm being unfair. I've also met some pretty whip-smart, thoughtful psych students and professors.

Small quibble: if the section describes a research design, it's methods. You can only call it methodology if it's a "meta" discussion about methods.

Post a Comment